Culture of the Democratic Republic of Congo

Congo is not only a “geological scandal” as many like to refer to it for its indescribable, enormous mineral wealth. It is also among those African countries where quality creative artists are found in abundance. Congolese art has also had a great impact on the work of Picasso. Observing from ethnic groups, languages, religions, literature, theatre, sculptures, masks, music and fashion, Congo is, without a doubt, one of the most remarkable and exceptional artistic centers that Africa has to offer.

Ethnicity and Language

Ethnicity, often called “tribalism”, was introduced in Congo by the colonialists in order to divide the people and prevent the rise of nationalism. Tribalism and regionalism were seen as the major causes of chaos and disruption following independence, and in the mid 1970s the N’sele Manifesto, the magna carta of Mobutu’s party, was created in order to eliminate tribalism from national politics and promote the ideologies of “authenticity”, which aimed at promoting and preserving Congo’s culture. At least 250 distinguishable ethnic groups live in Congo, speaking about 250 languages. Bantu languages are the most dominant and are spoken by 80 % of the population. French is the official language, used in business, legal, political and academic meetings. In addition to French, Congo has also four national languages – Kikongo, Lingala, Swahili, and Tshiluba, which can be considered as the regional lingua francas.

Religions (Spiritualism)

The majority of the Congolese population are Christians, comprising 46-48% Roman Catholics, and 26-28% Protestants. Kimbanguists may represent 16.5%, and Islam has a smaller number of adherents. Congolese traditional rites and beliefs are based on one supreme god with lesser and subordinate gods, or spirits and ancestors. The lesser spiritual beings serve as a link between the living and the dead. Other religions found in Congo include Jamaa and Kitawala. Kimpa Vita (known as the “black Joan-of-Arc), and Kimbangu were among the religious leaders or prophets who developed their own teachings based on Christian principles. They attracted so many followers that they became to be considered a danger by the authorities.

Literature

In terms of literature, Congolese writers have achieved recognition beyond national borders, joining the list of world-renowned poets and authors, and making their way into the spotlight. Among these writers are Léonie Abo, Patrice Lumumba, Thomas Kanza, Kama Kamanda, Maguy Rashidi-Kabamba, Amba Bongo, Clémentine Madiya, Faik-Nzuji, Antoine Roger Bolamba, Mutombo-Diba, Mwilambwe, Mushiete, Ghenzhi, Elebe ma Mikanza Mobyem, Diur N’tumb, Yoka Lyé Mudaba, Mutombo Buitshi, Pie Tshibanda, Elikia M’bokolo and many others. Other writers are emerging in the Congolese Diaspora, striving to highlight and expose the horrors and atrocities of a war that has plagued their country for 14 years, claiming the lives of over 6 million Congolese, frightening and pestering the population for control and exploitation of the land and its mineral wealth by multinational corporations, Rwanda and Uganda.

Theater

Theatrical arts are vibrant in the Congo, particularly in Kinshasa where a large number of groups flourished during the 1970s and1980s. Acting groups received major support from schools, universities, religious and social organizations. Many plays are written by local playwrights, but a few plays from international theater are produced as well. “Groupe Salongo” and “Minzoto Wela Wela” were among the most popular aside from the Théâtre National. “Authenticity” is very emphasized in productions, using African storytelling techniques, like “griot” or narrator, dream and fantasy sequences, and singing and dancing to the background of drums and musical instruments. When sponsored by the government or other organizations, the National Theater tour nationally and internationally.

Congolese Culture - Sculpture and Masks

Sculpture and Masks

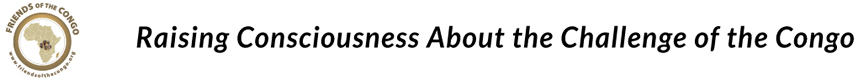

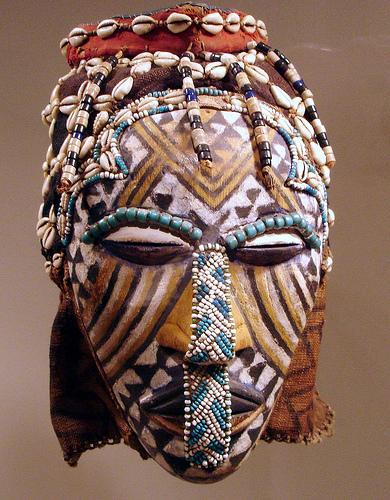

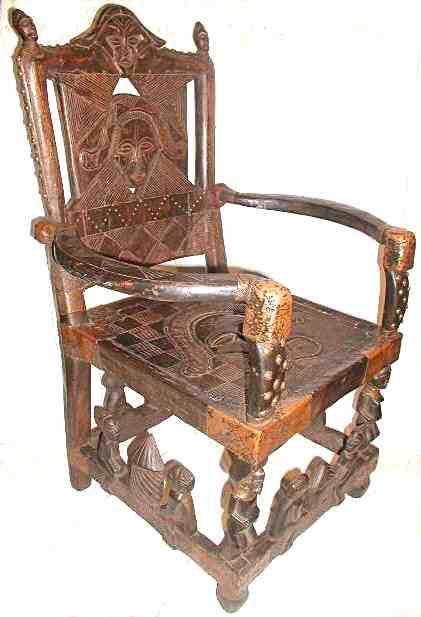

Congo, like most African countries, is known for its ancient sculptures and masks which can be seen in museums all over the world. The variety of art styles and the abundance of its production make Congo a center of exceptional artistic riches and one of the most remarkable in Black Africa in terms of traditional arts. The influence of Congolese sculpture on modern art and the cubism movement has been well documented. Pottery, basketry, textiles like raffia and wood carving are also part of main handicrafts of Congo. There are at least fifty different styles of sculpture, related to the tribes. They bear the name of the tribe where they were developed and where they were kept. The main ones are Kongo, Teke, Holo, Suku, Pende, Mbala, Ngbandi, Ngbaka, Azande, Mangbetu, Mongo, Mbole, Lengola, Kuba, Luba, Songye, Lega, Bembe, Hemba, Tshokwe. There are many other tribes that produce unique works of equal value. Wood is the most used material, then come ivory, bone, plant fiber, metal: stone. The cowry shells, beads, feathers, animal skins, kaolin and vegetable colors complement and decorate numerous works. It is important to note that traditional art is essentially functional. Many objects that reflect aesthetic is purely utilitarian. Modern art is also finding its mark in Congo, with self-taught and graduates of Fine Art Schools. Painting is another area where Congolese artists excel in, with renowned painters like Chéri Samba, Maludi Solo, Mongita Lokele and many others.

|

|

|

|

| Songye mask | Luba mask | Teke mask | Mangbetu Harp |

|

|

|

|

| Pende mask | Kuba mask | Tshokwe chair | Congolese painting |

|

|

||

| Copper Bracelet | Congolese statue |

The impact of Congolese Masks on Picasso

Picasso came in contact with the work of African artists at around 1905. This new form of art stimulated a great interest in him since it was different from what he was exposed to in the West. He was particularly fascinated with African Masks. After the great discovery he wrote:

“I have experienced my greatest artistic emotions, when I suddenly discovered the sublime beauty of sculptures executed by the anonymous artists from Africa. These passionate and rigorously logical religious works are what the human imagination has produced as most potent and most beautiful…”

At that moment, I realized what painting was all about!

Picasso was above all taken by the elements and principles of design applied on the masks in addition to the emotions that they transmitted. Captured by the power of these new forms, he begins to apply them into the preliminary sketches for Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon, from which originated Modern Art and the Cubist Movement.

The mask worn by the woman in the bottom right corner of Les Demoiselles d’Avignon is based on the Mbuya (sickness) Mask, created by the Pende of the D.R Congo, as revealed by art experts. It is noticeable that Picasso painted an unadulterated reflexion of this mask. All facial distortions and expressions created by the Congolese artist have been retained and faithfully reproduced. Interestingly, facial distortions and emotional expressions are what constitute the quintessential elements in both Les Demoiselles d’Avignon and the Mbuya Mask.

|

|

|

| Mbuya (sickness) Mask. Pende, Dem. Rep. of Congo |

Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon Pablo Picasso, 1907 |

Congolese Culture - Music and Fashion

Music

One of Congo’s greatest contributions to contemporary African culture has been its music, particularly the orchestra music that developed in the 1960s. The first authentic Congolese musicians were troubadors of the 1940s and 1950s, travelling to perform primarily in the more remote provinces. Among the early troubadors were Antoine Wendo Kolosoyi, Tête Rossignol, Paul Kamba, Polidor, Jean-Bosco and Colon gentil. They travelled as soloists but as the music developed, the solo acts became groups, adding African drums and acoustic guitars. Antoine Kasongo, Tekele (believed to be the first female music star), and Odéon Kinois were among the first leaders of groups. Traditional music was given up by younger generations as they were shifting towards new forms and adding more instruments.

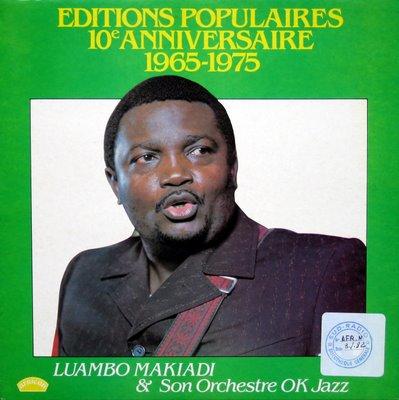

The first recordings of Congolese music were made by colonial museums in 1947. At about 1953, Joseph Kabasele, one of the founding fathers, formed the African Jazz Orchestra and made a few records. Luambo Makiadi Franco, the first to begin playing cha-chas, formed the O.K. Jazz Orchestra. The influence of Cuban and Latin music began to be felt in the late 1950s. A number of Latin American records were adapted and recorded by Congolese groups. These included “Kay-Kay”, “Son”, “Tremendo”, “L’Amor” , and “Lolita”. Most composition of songs in this period have Latin rhythms and Congolese lyrics with such classics as “Indépendance Cha-cha” by Tabu Ley Rochéreau to commemorate independence, and “Cha-cha-cha de Amor” by Luambo Franco. “Congo Jazz” is used generally to describe Congolese orchestral music, with Franco, Rochéreau, and Docteur Nico among the most popular musicians. The term “Soukouma” (Lingala for “shake”) had been introduced and gradually became the dominant form of music by the late 1960s. Congolese music has become one of the most popular in Africa by this time. By the late 1970s, as the number of bands had multiplied and the music considerably pluralized, some leaders incorporated disco, jazz, and blues harmonies into their compositions. Others preferred ballads and traditional musical forms. Although many languages were used in the lyrics, Lingala remained the most common. Several were created deriving from the African Jazz and OK Jazz, we can name Grand Zaiko of Manuaku, Viva la Musica of Papa Wemba, Choc Stars of Ben Nyamabo, Victoria Eleison of Emeneya JoKester, Quartier Latin of Koffi Olomide, Empire Bakuba of Pepe Kale, and the group Wenge Musica. This third generation of bands introduced new dances like Cavacha, Griffe Dindon, Caneton, Silauka, Kwassa Kwassa, Ndombolo etc.

Congolese music is most of all dance music, usually favored in large, open-air dance clubs. Kinshasa used to be one of the earliest recording centers in Africa, but economic hardships and shortages of foreign exchange led the industry to decline in the late 1970s, leaving space and opportunities for other African cities like Abidjan and Lagos. Congolese orchestras frequently perform and record in Paris and Brussels. A few better known artists and orchestras manage to tour or record in the Americas, including Werrason, Koffi Olomide, JB Mpiana, Fally Ipupa, Lokua Kanza, Mbilia Bel, just to name a few.

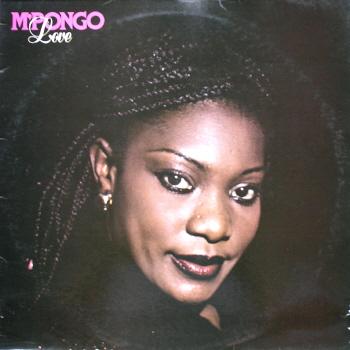

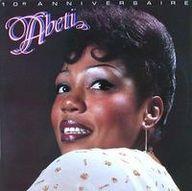

Abeti Masikini, Mbilia Bel, Tshala Muana, M’pongo Love, Yondo Sister, Faya Tess, Barbara Kanam are among the most popular female musicians who are celebrated throughout Africa and internationally.

The absence of a recording industry and a limited market for art has led a few artists to leave the country and settle abroad. Within this groupwe find popular artists like Papa Wemba, Emeneya JoKester, Awilo Longomba, Kanda Bongoman, Lokua Kanza, Makoma,Chico Mawatu, Alain Makaba,Reddy Amisi and many more.

Undoubtedly, Congolese have music in their blood; and it is one of the arts through which they’ve come to best express their outstanding creativity. The most striking fact is that most Congolese musicians are exclusively self-taught and exceptionally gifted.

|

|

|

| Lokua Kanza | Tabu Ley Rochéreau & Emeneya JoKester | M’pongo Love |

|

|

|

| Abeti Masikini | Luambo Franco |

Fashion

Everything about Congolese fashion revolves around the colorful print fabrics called “pagne”. The cloth, made in bolts two yards wide, is usually cut for resale into strips two to six yards in length. A staple of Congolese culture and dress, many prints are given a name. Some are designed and marketed for special purposes, like praising a leader, marking a special event such a summit meeting, soccer tournament, visit by a foreign head-of-state. Traditional aspects of theCongolese fashion have come to blend with influences from European or American fashion culture. This is most visible in urban areas where younger generations try to keep up with the trends.

Culture is everything; it is our way of life, and the most powerful strategy for the survival of any human society. In this era where global cultures are taking currency over the dying or decaying ones, it becomes imperative, not only to adapt to the macrocultures, but also to try to understand and inquire ways in which local cultures could be prevented from being suppressed or extinguished.