On June 27, 2025, the United States brokered a peace deal between the Democratic Republic of Congo and Rwanda; as part of it, thousands of Rwandan soldiers would withdraw from the DRC, and both states would develop a joint security mechanism. Following this, the foreign ministers of the DRC and Rwanda, alongside American Secretary of State Marco Rubio, officially signed a Declaration of Principles recognizing the boundaries of both nations and committing to “counter non-state armed groups and criminal organizations that threaten the Participants’ legitimate security concerns”. While American President Trump touted this as a major peace deal in the region, it included one major catch – as part of the deal, Congolese President Felix Tshisekedi conceded far greater access to Congolese minerals to the U.S., with this arrangement being referred to as “minerals for security”. This would mean that the United States would have far greater access to and control over mining operations in DRC, increasing imports of tin, cobalt, lithium, and copper at the expense of the people of Congo. This deal marks a recent increase in American presence and involvement in the DRC, but it isn’t fully new, either.

Shinkolobwe is a name foreign to most Americans, but its effects are very familiar. In 1915, Shinkolobwe became the site of radium mines and, more importantly, had vast deposits of uranium. While the presence of uranium, at first, was not as important, in 1942, this changed. The U.S. bought nearly 1,200 tons of uranium from the Belgian-owned mining company Union Miniere to be used as part of the Manhattan Project. This uranium would later be used in the development of the same nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The toll of the atomic bombs wasn’t limited to Japan. Operated by Belgium, minimal to no precautions were taken to protect the Congolese miners and the effects of this are seen today, although the U.S. no longer imports minerals from Shinkolobwe – birth defects are far more common in the region, and cities within the U.S. like St. Louis that processed the uranium from Shinkolobwe still experience higher rates of autoimmune disorders and blood diseases.

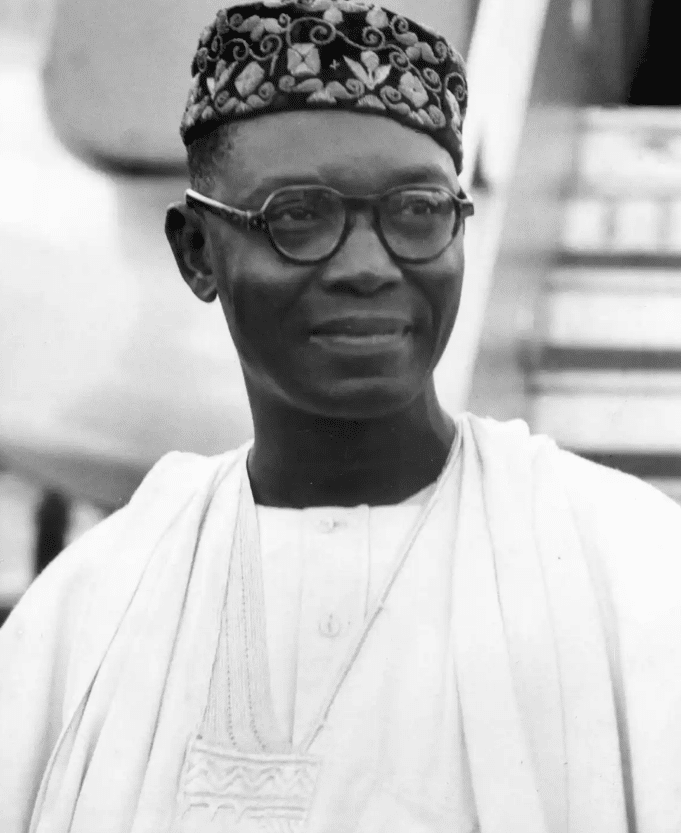

Donald Trump isn’t the first American president to be involved in the Congo as a whole, either. In 1960, President Dwight D. Eisenhower stated that he hoped that Patrice Lumumba, an independence figure and the first prime minister of the DRC, “would fall into a river full of crocodiles”. Later that same year, Eisenhower directed the CIA to assassinate Lumumba. Belgium had already been making efforts to destabilize the newly independent state of Congo – a few months before independence in 1960, Belgium privatized Union Miniere, retaining economic control of Katanga region, later helping their efforts to sow civil war between the region and Lumumba’s state – but these aims were bolstered heavily by the U.S. Secessionist leader of Katanga Moise Tshombe, for instance, received funding from the U.S. government. In Lumumba’s assassination, this collaboration was seen again.

In a meeting on August 18, Eisenhower advised CIA Director Allen Dulles to assassinate Lumumba. The U.S. proceeded by poisoning Lumumba’s toothpaste and food to kill him. In 1961, this wish came to fruition at the behest of a Belgian-backed firing squad.

Even after Lumumba’s assassination, the United States has remained deeply involved in Congo and in the exploitation of it. Within this very year, former President Joe Biden pushed and launched the Lobito Corridor project, which links various mining provinces in Angola, Zambia, and the DRC through an 800-mile stretch of railroad. Rather than benefiting Congolese people, the plan is focused on exporting minerals from the DRC; the center of the railroad is the ‘Copper Belt’, a region between Zambia and the DRC.

The recent deal has been met with scrutiny within the DRC, with many waiting to see what comes out of it. Michael Odhiambo, who works for Eirene, an international peace organization, in Uvira, DRC, has been critical of the deal in an interview with Al Jazeera. “There is fear that American peace may be enforced violently, as we have seen in Iran. Many citizens simply want peace, and even though this is dressed up as a peace agreement, there is fear it may lead to future violence that could be justified by America protecting its business interests.”

Although the U.S., unlike other imperial nations, never officially owned colonies in Africa, its consistent interference in the internal affairs of African nations, during and after the Cold War, as well as its exploitation of Africa as a whole, show that this was in name only. From direct CIA involvement in coups in Ghana and Congo to their efforts to undermine revolutionary leaders like Thomas Sankara in Burkina Faso to the economic exploitation of today, the U.S. was and is as much of an imperialist force in Africa as the U.K. and France.

Written by Vernon Demir