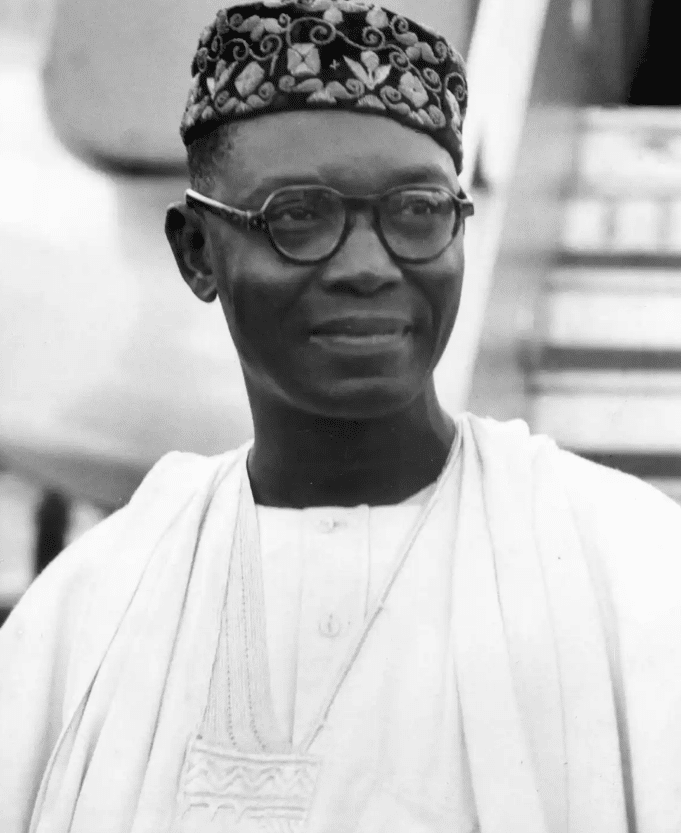

Front-and-centre, or side-by-side? The question of the Congo’s place in African anti-colonial struggles has varied in answer from thinker to thinker. As covered previously, Nkrumah, the first President of Ghana, believed that the Congo stood as the “Heart of Africa” and was therefore at the forefront of African liberation. However, not every thinker shared this opinion and instead believed that the Congo’s place was on a more equal level of importance to its neighbours. One such thinker was Nnamdi Azikiwe, the First President of Nigeria and the father of Nigerian nationalism.

Nnamdi Azikiwe (1904-1996) was born in Zungeru in Niger state to Igbo parents. Attending primary and secondary schools in Onitsha, Calabar, and Lagos, Azikiwe was exposed to all three major Nigerian cultures, learning more about Nigeria’s position in the world upon moving to the US for university and later travelling to Ghana for early employment. After returning to Nigeria in 1937, Azikiwe founded the Nigerian Youth movement and the National Council of Nigeria and the Cameroons (NCNC) which supported him as he was elected to the Nigerian Legislative council and later emerged victorious during the 1959 federal elections. These elections were key in securing Nigerian independence from the United Kingdom’s colonial control, asserting Nigeria’s capacity for self-rule, and demonstrating their demands for freedom from European imperialism. Despite his focus on Nigerian politics, Azikiwe also looked outwards to the rest of Africa, foreseeing a collaborative push between African states for the total liberation of the continent from colonial powers.

Azikiwe’s anti-colonial thought rested on a few principles, insisting upon the right of an African state to sovereignty, non-interference, and to federate (or confederate) with whom they chose. The state of African nations was a source of despair for Azikiwe, who likened the continent to a “ham which has been carved by the sword of European imperialism.” The Nigerian leader believed that if matters were placed totally and wilfully into the hands of African countries by Europe, the continent would prosper. Most importantly, Azikiwe believed in the right of African states of equality of sovereignty irrespective of size and population, opposing any hierarchy of importance between African countries. For these foundational beliefs, Azikiwe believed that the independence of Africa came from the formation of an African Leviathan from a collaboration among African states, calling for Nigeria to “co-operate closely with the other independent African states” to form the political bloc needed to push out colonial influences. While still supportive of African liberation and the Congo’s independence, Azikiwe’s ideals put an emphasis on equal collaboration among African states as the method towards true African freedom, instead of the fateful sway of any state, as Nkrumah believed for the Congo.

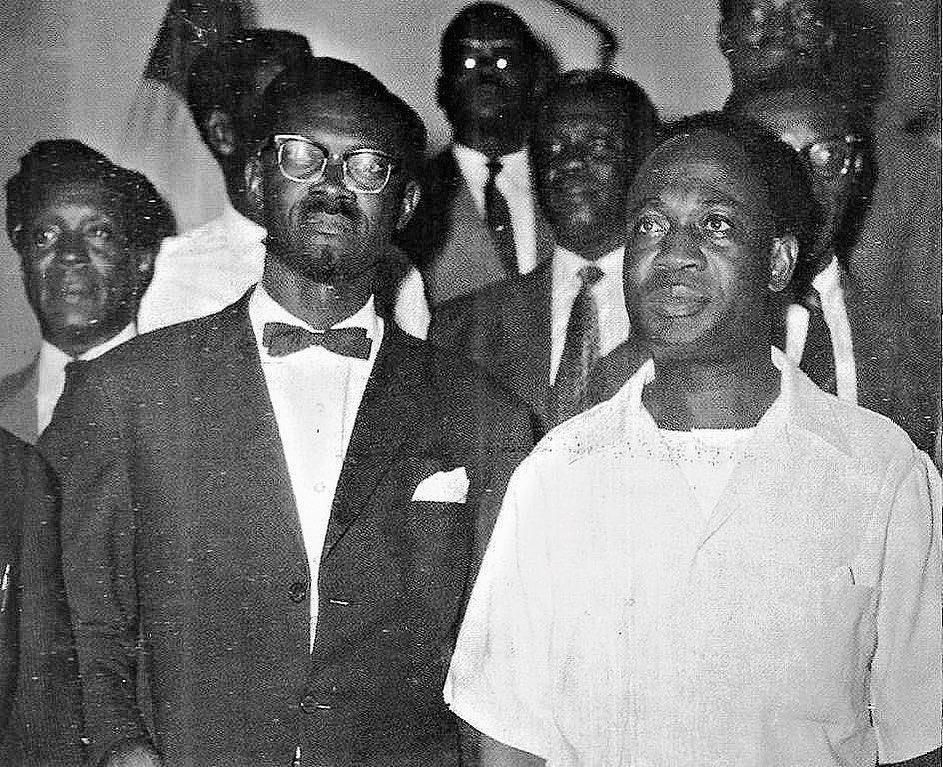

Lumumba’s own philosophy aligned with much of Azikiwe’s thought, similarly believing in an egalitarian attitude to the importance of African Liberation. In a speech at the University of Ibadan, Nigeria, in 1959, Lumumba stated that “Africa will not be truly free and independent as long as any part of this continent remains under foreign domination”, placing all African states on an even plane of importance. The Congolese leader was also of the same opinion that it was colonialism and its facets of control that “seriously hinder the flowering of a harmonious and fraternal African society,” seeking their removal to allow Africa to bloom. Lumumba similarly sought the unity of Africans in popular movements or unified parties to “demonstrate our brotherhood to the world” and fight against the balkanisation of Africa into weak states at the mercy of the West, a sentiment parallel to Azikiwe’s own comparison of a balkanised Africa to a carved ham in its revulsion at the predatory colonial division of Africa.

While Azikiwe’s thoughts on the Congo Crisis itself remain unknown, it can be assumed through his philosophy, that the secession of Katanga under Tshombe and the brutal military involvement of Belgium, the UN and allied countries would have been taken as a mark of disrespect to the integrity of Africa and its right to federate or confederate without influence. The involvement of Nigerian military forces in peacekeeping operations solidifies notions of favouring an Africa-led response to intra-African conflict and the camaraderie of African states through the support offered to the Congolese government by Nigerian forces.

Despite records never hinting at a meeting between the two leaders, Azikiwe and Lumumba clearly shared a vision of an Africa free from European domination and believed in similar pillars for African inter-state collaboration moving forward. Whether the vanguard of liberation or a willing member of an egalitarian community, the Congo’s independence was and is a matter of importance to Pan-Africanists from all walks of the ideology. Today, the Congo faces the same challenges to its rightful sovereignty, territorial integrity and freedoms as it faced during the crisis of the 60s. Irrespective of which pan-Africanist ideologue you follow, there is no question about the independence of the Congo; its protection is essential to the anti-colonial struggle, and it must be freed from the grasp of colonial and neo-colonial influences.

Written by Alex Temmink