In considering how to proliferate development efforts and unity in a country, peacebuilding is looked upon as an integral part of reconciliatory processes in contexts of war and violence, particularly where injustices have occurred. Many of these injustices directly affect women who are treated as worthless pawns amidst political games, gambles, and conflicts. Yet, on the topic of peacebuilding in Congo, the treatment of women amidst conflict and generally in society is not foregrounded as a key element when thinking about reconciliation, memory, and moving forward. Much less discussion around peacebuilding. The DRC has seen multiple failed attempts at peacebuilding strategies, and such a recurrent outcome has raised questions concerning the sincerity of the multiple state and non-state actors involved in fostering peaceful dialogues. Recently, however, the light at the end of the tunnel seems to be more than a faint haze for the Congolese. Recent days have seen an unprecedented union between President Felix Tshisekedi of the DRC and politician Martin Fayulu, who fancied himself something of an opposition leader. Where a scathing attitude to Tshisekedi’s presidency was entrenched in Fayulu’s political discourse, as he believed his ‘electoral win’ was stolen from him by Tshisekedi in 2018, his contestations seem to have taken a turn, as both Fayulu and Tshisekedi have now found themselves in coalition against the endeavours of Joseph Kabila. Former president of the DRC, Kabila, continues inciting discord between Congolese people and working in alliance with Rwanda to portray the situation in Congo as a display of internal Congolese bickering, absolving Rwanda of its culpability and involvement.

Whether a ruse or a genuine desire for a partnership, Tshisekedi and Fayulu’s meeting may well mark a critical juncture in Congolese politics; this coalition sends a message throughout the country that being unified by a shared national identity and a desire for Congo’s development should trump the tribal tensions that have long constrained development in many areas and at various levels of society.

One of the most striking points raised in the dialogue was Fayulu’s call for “national cohesion”, expounding on the need to create a “camp for the homeland” which would prioritise the urgent needs of the Congolese people, concerns. This is particularly interesting in light of the peace agreement between Rwanda and the DRC. Where some have praised the efforts to get Rwanda to the negotiation table and reach a shared conclusion, others have condemned the agreement as a pitiful transaction that resulted in Congo being sold to America, just through a ‘legal framework’. A country that, prior to this, had been effectively ‘sold’ to Rwanda, at the hands of former president Joseph Kabila. This peace deal, signed on the 27th of June 2025, poses an interesting question as to whether such actions promote “national cohesion” and “creating a camp for the homeland”. Such an endeavour would require the support of all the Congolese people, irrespective of their tribal background, often a catalyst for conflict and flailing social cohesion. Yet, amidst all this discourse concerning ‘Congolese interests’, one must ask: do these interests include upholding the rights of women in zones of conflict? Whilst this meeting could later be looked back upon as having marked something of a critical juncture in the DRC’s development trajectory, this meeting may keep our eyes fixed on potential promises not yet realised and distract our attention from the ever-present tragedies occurring outside Kinshasa. Maintaining hope and optimism about the DRC’s political situation should not replace our continued efforts to raise awareness about the particular suffering of women and girls who are repeatedly subjected to violations and human rights abuses by the Rwandan-backed M23 rebel group and other Rwandan actors in eastern Congo.

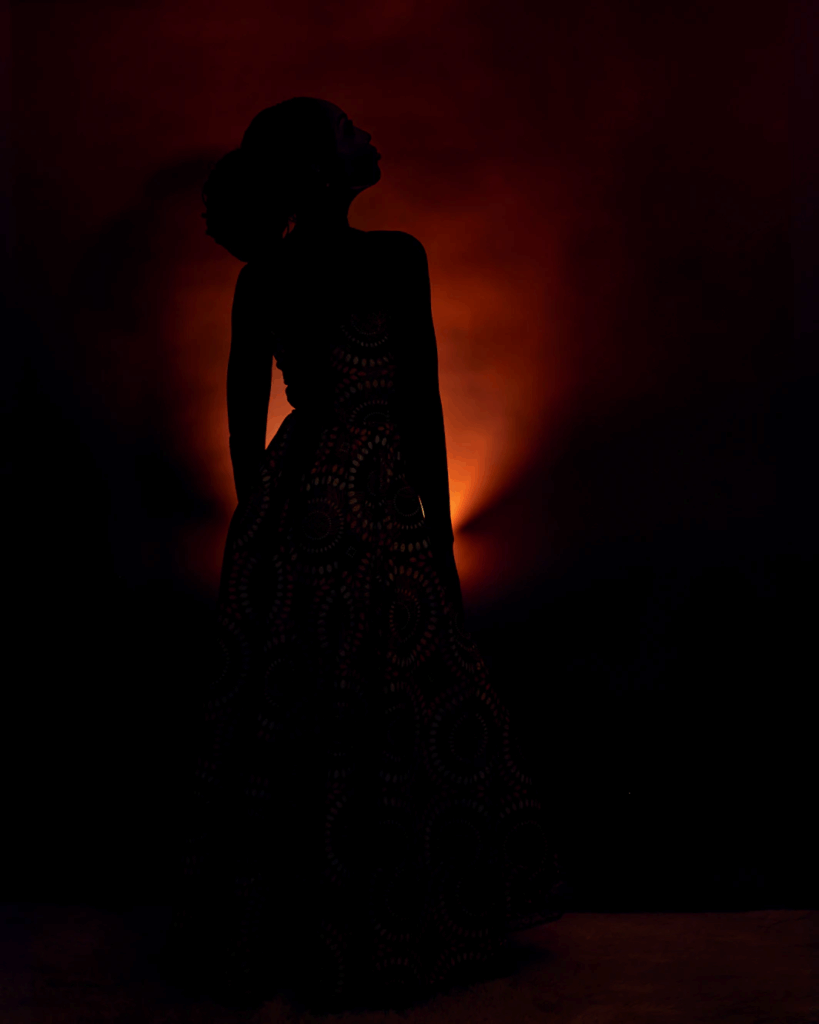

A recently distributed clip showed a Congolese woman from Goma lying on the ground and held down by a group of men. What ensued was a display of physical violence with makeshift wooden batons as her punishment for refusing to be forcibly married to a Rwandan. Not only did she receive continuous blows on her back downwards, but she was also robbed of her dignity as parts of her genitalia were exposed on camera whilst she received blows from the wooden sticks. With all the people gathered to watch the affair, whether forcibly or not, no one stepped in or up to rescue her from what will remain a harrowing memory for her and those around.

Such is the suffering of many women who live in areas at the heart of the conflict, only the world does not bear witness, particularly as they are not all recorded or reported. In some conflict-ridden areas in the DRC, no regard is given to women’s rights, with statistics detailing that a woman is raped every 48 hours in the DRC! Women do not seem to be a priority in Kinshasa’s political discourse, and thus, women are left to the devices of rebels and groups like the Rwandan-backed M23. Organisations like the Panzi Foundation, which helps women who have been victims of sexual violence in conflict situations and sexual war crimes, need to be foregrounded in the discussion about helping women. The organisation aids women in reclaiming their narratives and rebuilding their lives, an element of particular importance as many survivors become ostracised by their communities, though they have suffered. These women are indeed worth more than their harrowing experiences, and in wanting governments to materialise their support for these women, the de-stigmatisation of women who have been subjected to such crimes must accompany any support given. For instance, should the government enforce laws creating a police department for the reporting of sexual violence, without de-stigmatisation, crimes would likely remain unreported due to the shunning and shame that women would be met with! The prevailing situation across the DRC’s political landscape highlights a disconnect between the government and its people. Where the current administration has made significant progress in areas like education, the government’s priorities do not always seem to align with or wholly consider the critical needs of certain groups in society, like women.

Due to a ‘lack of public and official data concerning gender-based violence and violations carried out against women and girls’, as reported by Amnesty International in 2024, many cases of violence against women are disregarded. This only harbours a sense of impunity across the country and sends a message that supporting women’s rights is not critical to the nation’s development, encouraging ignorant attitudes and carelessness. Clearly, established international human rights law has little effect in regions like Goma! It remains imperative that the Congolese government is lobbied to take expedient actions to support affected women in these conflict-ridden parts. Women are key to Congo’s development, and neglecting their rights is erroneous in every way.

The understanding of development presented within this article is drawn from the writings of Thandika Mkandawire. His work describes development as the “liberatory human aspiration to attain freedom from political, economic, ideological, and social domination. As highlighted by much research, women are pivotal to development efforts and economic prosperity in developing countries. For example, fostering safer environments for women to exist means that women in developing contexts (and more generally) would willingly engage in different forms of work available, even in male-dominated spheres. This leads to economic diversification, as well as an improved quality of human capital. To successfully support women in areas like Goma, mechanisms must be established that enforce women’s safety and accountability measures for those who threaten this. For women who suffer in the aftermath of abuse, a reform in the judicial system is crucial in helping such women obtain justice and support in rebuilding their lives and reintegrating them into society. This is because many women who face sexual violence are often ostracised by their communities and shunned.

People are the most important part of development efforts, and therefore, where issues concerning the people are not handled, real development cannot really be obtained. This also speaks to the importance of social policy that can ensure the inclusion of diverse groups in development efforts and society overall. Women in Congo require government attention, and without this, armed groups and even general civilians will continue to wage war on women’s rights and lives.

The war on women must end. This war does not rage only in Congo’s zones of conflict, but across the nation. A more prominent discussion on how to combat this war on women is crucial to millions of female lives being protected in the DRC, and whilst activist groups and charities may provide limited support, one way in which long-term change can be effected is through government intervention. As you consider the ongoing situation in the DRC, remember the millions of women who often face the repercussions of political issues, becoming retaliatory tools at the hands of rebels and finding themselves with no one to turn to.

Written By Ketsia Kasongo