If touched upon within education, African anti-colonial thinkers are often placed in a political vacuum, artificially isolated from neighbouring contemporaries within wider continental dialogues. The effects of collaboration among African ideologues on pan-Africanist thought are often left out of records, constructing a false atmosphere where African anti-colonialists acted alone against European imperialism instead of together. This phenomenon risks the omission of key interactions between popular African leaders and the connections made between their struggles for independence.

Notably, Nkrumah, the revolutionary first President of Ghana, was a marked supporter of Lumumba and a Free Congo. Nkrumah is construed as the founding father of Ghana and the main leader behind Ghana’s role in the wider pan-Africanist movement, but little is said about his interactions with fellow leaders. Nkrumah saw the Congo as “the Heart of Africa” – a vital region that formed a buffer state between a growingly independent Africa in the North and a South controlled by imperialists. To Nkrumah, the Congo stood as a decisive factor in the fight between neo-imperialism and Pan-Africanism, marking the victory of either party depending on which way the country swayed. Resultantly, the freedom of the Congo from imperialist influence became a matter of significant importance for Ghana’s president and Pan-Africanism at large, underwritten by the leader’s “fervent hope” to rally Africa to his ideology.

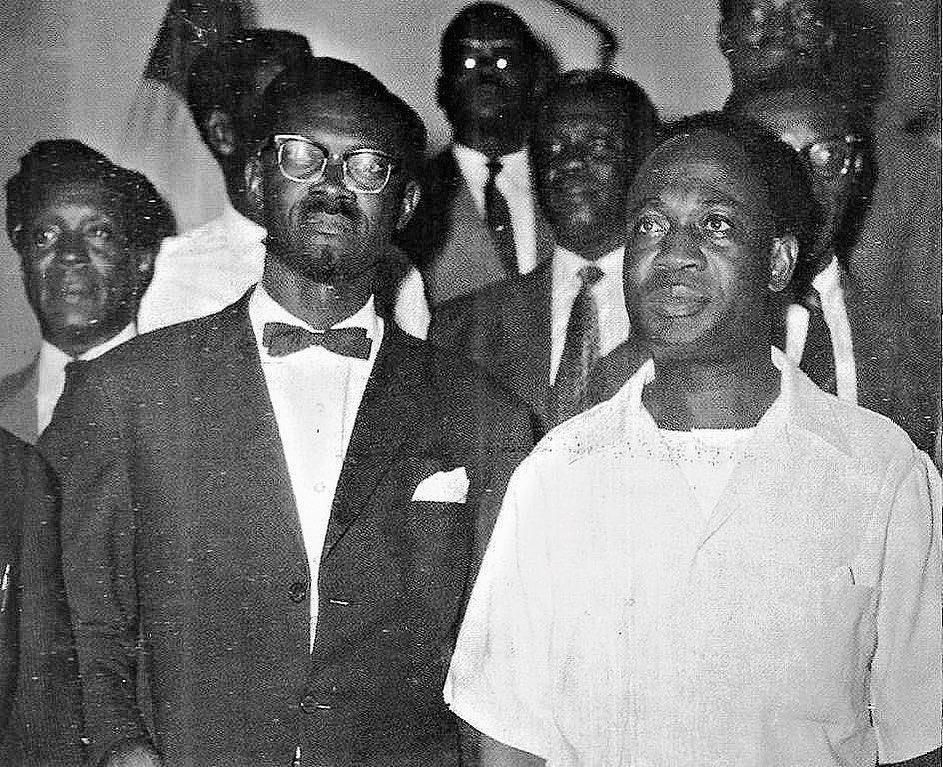

This political leaning brought Nkrumah into close contact with Patrice Lumumba, who shared in his ideals of African freedom, unity, and independence. Lumumba’s own experiences in Accra during the All-African People’s conference of 1958 had added a stark Pan-African dimension to his Congolese nationalism and fostered a close relationship between him and Nkrumah, referring to one another as brothers in official correspondences. Lumumba and Nkrumah often discussed how the Congo could be structured to best repel imperialist influence, with Nkrumah often encouraging a strong unitary governmental system for the Congo as a means of preventing neo-imperialist meddling through the exploitation of federal systems, an omen for events soon to come.

During the Congo Crisis of the 60s, Nkrumah attempted to push for “African self-respect” in peace-keeping matters by sending a solely African force to prevent conflict, also transporting an unprecedented level of foreign aid to the Congo at “almost every level of government”, according to Opoku Agyeman, including medical and civic support. To the Ghanaian president, this backing was a matter of principle, stating in a 1960 UN General Assembly meeting that “to damage the prestige and authority of that [Lumumba’s] government would be to undermine the whole basis of democracy in Africa”, denouncing the belligerence of the West and Western-backed rebels against the legitimate central Congolese government as an extension of how far colonial powers would go to maintain their domination “in one form or another in Africa.”

Nkrumah’s plans of an Afro-centric response to the Congo Crisis were short-lived, eventually being pushed out by a mix of UN, European, US, and US-backed forces who chose to support Mobutu and his pro-western sentiments. The betrayal of the UN and Lumumba’s later assassination at the hands of these parties was a source of considerable grief for Nkrumah, stating in a broadcast on the 14th of February 1961 that the loss of Lumumba was an illegal power grab by the rulers of the US, UK, France and other powers allied with Belgium as well as a “loss for the whole African continent.”

Despite knowing each other for a short time, the interactions between Lumumba and Nkrumah appeared to have a profound effect on the politics of Ghana, Congo and continental Pan-Africanism, highlighting an often-overlooked connection between African struggles to be rid of colonial influences. What’s important to keep in mind when analysing the Congo or any other Black African nation is that their struggles rarely exist in a void and are often emblematic of larger conflicts, be it ideological, economic, or social. The Congo is the heart of Africa, so ask yourself, what does it tell you when the heart is under attack?

Written by Alex Temmink