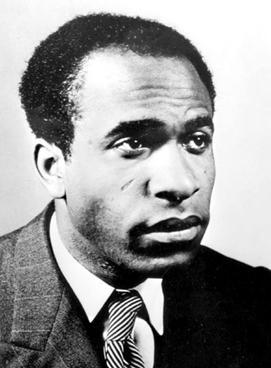

“Africa is shaped like a revolver, and the Congo is the trigger” – These are the words of French West Indian psychoanalyst, Marxist philosopher, and Algerian revolutionary, Frantz Fanon. When spoken about, Fanon is remembered for his contribution to anti-colonialist efforts against France in Algeria, and his written works covering the psychological and social trauma on the colonized caused by colonial rule. While these feats are noble and, in the case of Algerian independence, crucial against the psychological end of anti-colonial struggle, it is also important to keep his writings on the Congo and its place in African liberation in running conversation as they offer apt insight on how colonialism affected political power balances in central and southern Africa. Considering the recent crisis, this urgency has only grown, as the themes of colonial control mentioned by Fanon are observable in recent interactions between the Congo, Europe, the UN, Rwanda, and Uganda, and offer explanations for the nuances of current African power relations.

For background, Fanon was born in 1925 in the French colony of Martinique to a mixed-race, middle-class family. This unique circumstance exposed Fanon to the reality of colonial life, both the benefits of the system of the ruling and compliant classes, through his attendance at the prestigious Lycée Victor Schoeler school, as well as the costs incurred on colonized livelihoods through his Afro-Caribbean heritage. Despite this early awareness and anti-colonial education through his tutelage by Aime Cesaire, Fanon initially subscribed to the French colonial image, joining the 5th Antillean marching Battalion as part of the Free French Forces (FFL) in World War 2. During his service, Fanon became increasingly disillusioned by the racial discrimination propagated by both the FFL and Vichy France, stating in a letter to his brother Joby that he had been “deceived” by the ‘honourable’ struggle of the French and was sick of it. Following the Second World War, Fanon studied literature, drama, and philosophy at the University of Lyon shortly before doing a residency in Psychiatry at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole. This education led to Fanon’s eventual station at Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria, where Fanon’s disillusionment spilled over into open opposition following his disgust at the enforcement of colonial norms despite their clear mental effect on hospital residents. After handing in his famous “Letter of Resignation to the Resident Minister,” Fanon joined the FLN, aiding in efforts to free Algeria from French occupation through writing and ambassador work, primarily to Ghana. Fanon continued this line of work until his leukaemia diagnosis, going to the US for medical treatment in a deal with the CIA made at the request of his comrades. Fanon’s sudden death in 1961 from double pneumonia, which he contracted during his abandonment in a hotel by his assigned CIA operative, cut the career and life of Fanon short, but his place in Algerian liberation and wider Africanist thought has preserved his memory.

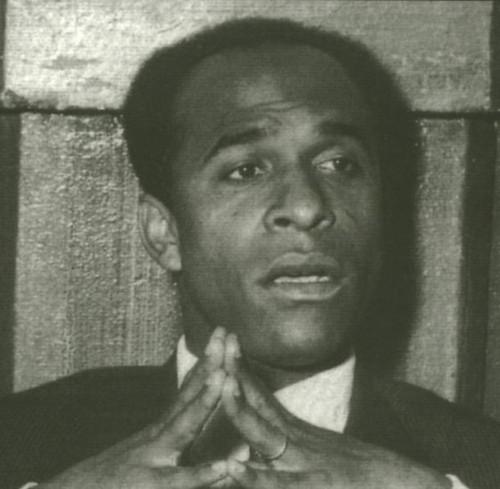

Fanon wrote extensively in praise of both the Congo and Lumumba, supporting Lumumba’s mission “to liberate his people and make sure that his people no longer lived in great poverty and indignity, despite the riches of the Congo.” The writer also had a high reverence for the music of Congo, depicting it as a strong, beautiful representation of wider Black/African culture unfathomable to the white man. Musical talent was not the only quality of the Congo that Fanon praised, remarking on the profound sense of unity among peoples fostered within the nation through Lumumba’s leadership. It was his stark belief that if any tribal dissensions remained in the Congo, it was because they were kept up by agents of colonialism. These agents of colonialism were numerous, spanning from European states to the UN and all the way to rival African puppet governments. Primarily, Fanon believed these agents sought to spark rebellion by funding and arming the “lumpenproletariat,” the lazy, unemployed, and criminal elements within Congolese society, to sow dissent. These groups eventually formed the rebel armies of Kasai and Katanga.

Although initially called in as a peacekeeping force, Fanon was strongly against the intervention of the UN in the Congo, calling the organisation a “legal card used by the imperialist interests when the card of brute force has failed” in his book “Toward the African Revolution.” A unified Congo under Lumumba, to Fanon, ran counter to European interests in Central and Southern Africa, as Lumumba had proclaimed that the complete independence of the regions would follow the liberation of the Congo, dedicating support to nationalist movements in Rhodesia (Zimbabwe) and Angola. This threatened the material interests of the European empires, which had massive ambitions in extracting the vast abundances of resources, such as gold, rubber, and diamonds, from Africa. Their desperation only doubled following realisations that Lumumba was dedicated to his cause and could not be bought unlike the many “chiefs of puppet governments, amid their puppet independence” that Fanon observed populating African governments. The UN and its bias of power to the West then formed a perfect cover for Europe and affiliated parties to undermine Lumumba. Specifically, Fanon spoke about how the independent development of the Congo threatened Belgian interests, seeing the UN as its guarantor for sabotaging Congolese efforts towards furtherment. The UN was used as a cover by Belgian soldiers to commit atrocities, as well as a safety buffer by Belgian-funded enemies of the Congolese state to arouse public opinion against Lumumba in key regions such as Katanga. During this the UN also proved incapable of “validly settling a single one of the problems raised before the conscience of man by colonialism” or stopping any of the many massacres that took place during the 60s Congo Crisis, furthering notions of its biased and ineffective involvement.

Fanon’s denunciation of the UN for its shallow and Eurocentric involvement in the Congo during the 1960s crisis is poignant, given the current opinion of the UN’s continued presence in the country. In ‘Le Monde diplomatique’, Sabine Cessou writes how, despite the investiture of up to $1.3bn between 1999 and 2016, the deployment of 22,400 personnel in the DRC and the continued support of the UNSC in the Congolese “stabilisation” mission since 1999, the UN has failed to “prevent massacres or check the proliferation of armed groups” in the east, particularly the Rwanda-backed M23 group. Furthermore, the UN has maintained its presence in the Congo, despite its council voting for an end to MONUSCO, the UN’s peacekeeping mission in the DRC, in January 2024, extending its mandate to December 2025 in the face of M23 violations of the ceasefire agreement in North Kivu. Such decisions are insulting given their documented history of failing to prevent M23 from arming itself, as well as their blatant ignorance of repeated demands from Kabila during his presidency for UN withdrawal, as well as current President Félix Tshisekedi’s push for a complete withdrawal of MONUSCO by the end of 2024. The UN’s continued lack of interest in maintaining the peace despite its constant insistence on involvement was best highlighted by its inaction to break up clashing protestors and police outside the home of opposition leader Etienne Tshisekedi in August 2016, showing a willingness to overlook clear-cut cases of political violence. This often-lacklustre involvement in Congolese politics ensures one thing: that the Congo is kept weak, a condition beneficial to Ugandan, Rwandan, and European interests in a mirror image likeness to the benefits destabilising the Congo had to Europe during the crisis of the sixties.

Overall, Fanon held the Congo in high regard, praising its anti-colonial unity under Lumumba as well as its musical prowess. His criticisms of the involvement of the UN in the Congo as an ill-disguised intrusion of imperial interests in domestic Congolese politics still hold water today, as evidenced by current reactions to the UN’s continued presence in the DRC. One thing to note is that, despite despairing at the loss of Lumumba, Fanon encourages hope in the face of opposition to Congolese unity, stating that “no one knows the name of the next Lumumba.” Just as Fanon held hope for the Congo in the sixties, we should have the same hope for the Congo now, as with effort and drive, the liberation of the country from colonial invasion is a question of when, not if.

Written by Alex Temmink