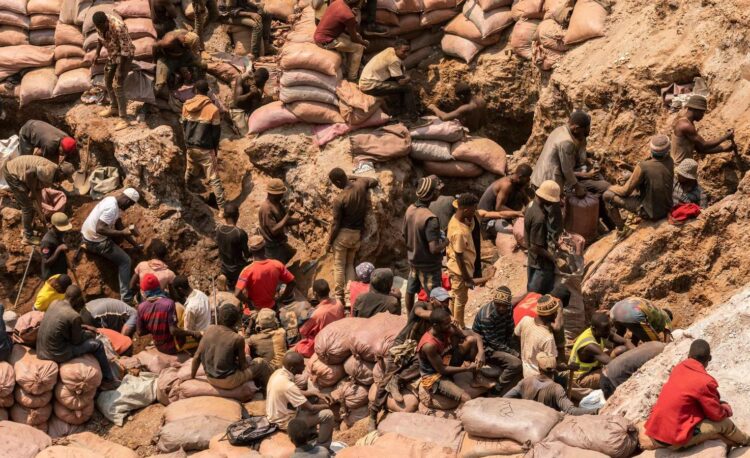

“I thank God for taking my babies. Here, it is better not to be born.” Priscille, a young Congolese woman, stated in an interview with Siddharth Kara (Cobalt Red, pp. 58). Priscille works as a miner in the Democratic Republic of Congo’s artisanal mining industry, an industry that, through the extraction of cobalt and lithium from the DRC, has made a fortune. 22.7 million sales of e-cigarettes in 2022 in the U.S. alone, 1.1 million sales of electric bikes in 2022, $60.6 billion worth of sales in laptops alone as of 2025 – all of these sales rely on lithium or cobalt, two minerals sourced partially and primarily, respectively, from Congo, and all of these sales result in wealth for nations in the Global North, not for the DRC or Congolese workers. Priscille, for instance, is only paid $0.80 for each fifty-kilogram sack of cobalt, another mineral source of batteries commonly used for electric products.

These batteries, relying on lithium, cobalt, and coltan for batteries, are often used as ecologically friendly alternatives to fossil fuels, used in products from e-bikes to electric cars. The effect on the DRC itself, however, is anything but ecologically friendly. Just as the global North benefits from the economic exploitation of the global South and other underdeveloped nations, nations like the DRC suffer greatly from both the climate impacts of fuel combustion from wealthy nations and, more relevantly, the ecological impact of the mining of minerals extracted from it. This impact isn’t just a statistical one; it’s a human one.

As far back as 2007, high amounts of radioactive pollutants were found beside mines in the DRC. In November of 2007, nearly 19 tons of radioactive materials were found dumped into the Mura River, resulting from copper and uranium mining. Cobalt mining, likewise, has resulted in contamination of nearby water sources: in Tshangalale Lake, close to cobalt mining towns, fish were found to have high levels of cobalt within them. Cobalt is, much like uranium, another radioactive material, adding to the contamination of drinking water and marine ecosystems.

These impacts aren’t limited to the environment or ecosystem – a study conducted in Lubumbashi in 2020 found that children of fathers with mining-related jobs were far more likely to have birth defects. In particular, exposure to toxic metals and minerals from mining increased the risk of developing conditions such as spina bifida and anencephaly. For the workers as well, the health impacts are drastic. Respiratory illness is particularly common due to exposure to air pollutants while mining, particularly radon, which has been known to cause lung cancer. Cobalt mining, as well, has been linked to pulmonary tuberculosis.

The Democratic Republic of Congo isn’t the only nation where cobalt, coltan, and similar minerals are mined, even if it is where the exploitation is the most severe. Thus, it isn’t the only nation to suffer as a result of it. In Chile, Calama, which has been home to major copper mining, has three times the number of lung cancer incidences when compared to the nation as a whole. The issue of the exploitation in Congo isn’t one of particular minerals: it doesn’t matter whether or not it’s cobalt, copper, uranium, or lithium being sourced from the Congo. It doesn’t matter whether or not these minerals are being extracted for seemingly ‘environmentally conscious’ reasons. It doesn’t even matter who is doing the mining, as adults are not spared from the health impacts. This issue isn’t just an issue impacting Congo, or even an Africa-exclusive issue; imperialism in the DRC is a global issue and should be treated as such.

Written by Vernon Demir

References:

- https://dn720002.ca.archive.org/0/items/siddharth-kara-cobalt-red-how-the-blood-of-the-congo-powers-our-lives-st.-martin/Siddharth%20Kara%20-%20Cobalt%20Red_%20How%20the%20Blood%20of%20the%20Congo%20Powers%20Our%20Lives-St.%20Martin%27s%20Publishing%20Group%20%282023%29.pdf

- https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2023/p0622-ecigarettes-sales.html

- https://www.energy.gov/eere/vehicles/articles/fotw-1321-december-18-2023-e-bike-sales-united-states-exceeded-one-million

- https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/Articles/Radioactive-ore-dumped-in-DRC-river

- https://spheresofinfluence.ca/coblat-mining-drc-green-technology/

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanplh/article/PIIS2542-5196(20)30059-0/fulltext

- https://issafrica.org/iss-today/child-miners-the-dark-side-of-the-drcs-coltan-wealth

- https://publications.ersnet.org/content/erj/60/suppl66/3709

- https://www.climatechangenews.com/2024/12/17/doctors-raise-alarm-on-childrens-health-crisis-in-chile-copper-mining-heartland/